What Is Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)?

Ever wondered what it really costs to make the products you sell? That’s exactly what Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) tells you.

Think of it as the price tag for producing your inventory. It covers all the direct costs—like raw materials and the hands-on labor needed to create your goods—but leaves out the indirect stuff like marketing or your office rent. Getting a handle on this number is the first, most crucial step toward understanding your real profitability.

What Is Cost of Goods Sold, Really?

Let’s make this simple. Say you run a small bakery. Your COGS would include the money you spend on flour, sugar, eggs, and all those chocolate chips. If you pay a baker an hourly wage specifically to mix the dough and bake the cookies, that’s part of COGS too. Why? Because these costs are directly tied to creating the final product you’re selling.

But what about the electricity for the oven? Or the rent for your shop? Those don’t count. Neither does the salary for the person running your Instagram account. Those are all considered operating expenses—the costs of keeping the business running, not of making the actual products.

It can get a little tricky telling the two apart, especially when you’re just starting out. Let’s break it down with a quick comparison.

COGS vs Operating Expenses Quick Comparison

This table clearly separates the direct costs of making your products from the indirect costs of running your business.

| Expense Type | Included in COGS? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Materials | Yes | Flour for a bakery; wood for a furniture maker |

| Direct Labor | Yes | Wages for assembly line workers |

| Production Supplies | Yes | Glue, nails, or packaging directly used on a product |

| Marketing & Advertising | No | Social media ads, billboards, influencer campaigns |

| Rent & Utilities | No | Monthly rent for your office or storefront |

| Salaries (Admin) | No | Pay for your accountant, HR manager, or receptionist |

Knowing this difference isn’t just for your accountant—it’s a game-changer for how you see your business’s financial health.

Why This Distinction Is So Important

Separating these costs is one of the smartest things you can do for your business. When you know your COGS, you can:

- Price your products intelligently. You’ll know the baseline cost you need to cover, allowing you to set prices that guarantee a healthy profit margin on every sale.

- Spot production problems. Is your COGS creeping up month after month? That’s a red flag. It could mean your material suppliers are charging more, or there’s waste somewhere in your process that needs fixing.

- Manage inventory like a pro. COGS and inventory are two sides of the same coin. A clear view of your costs helps you make better decisions about how much stock to carry, so you don’t tie up cash in products that aren’t selling.

In the end, COGS isn’t just some boring accounting term. It’s a powerful tool that gives you a clear-eyed view of your business’s efficiency and profitability, one product at a time.

The Simple Formula to Calculate COGS

You don’t need to be a math whiz to figure out your Cost of Goods Sold. Honestly, it all comes down to one simple formula that gives you a clear picture of how your inventory moved over a certain period, whether that’s a month, a quarter, or a year.

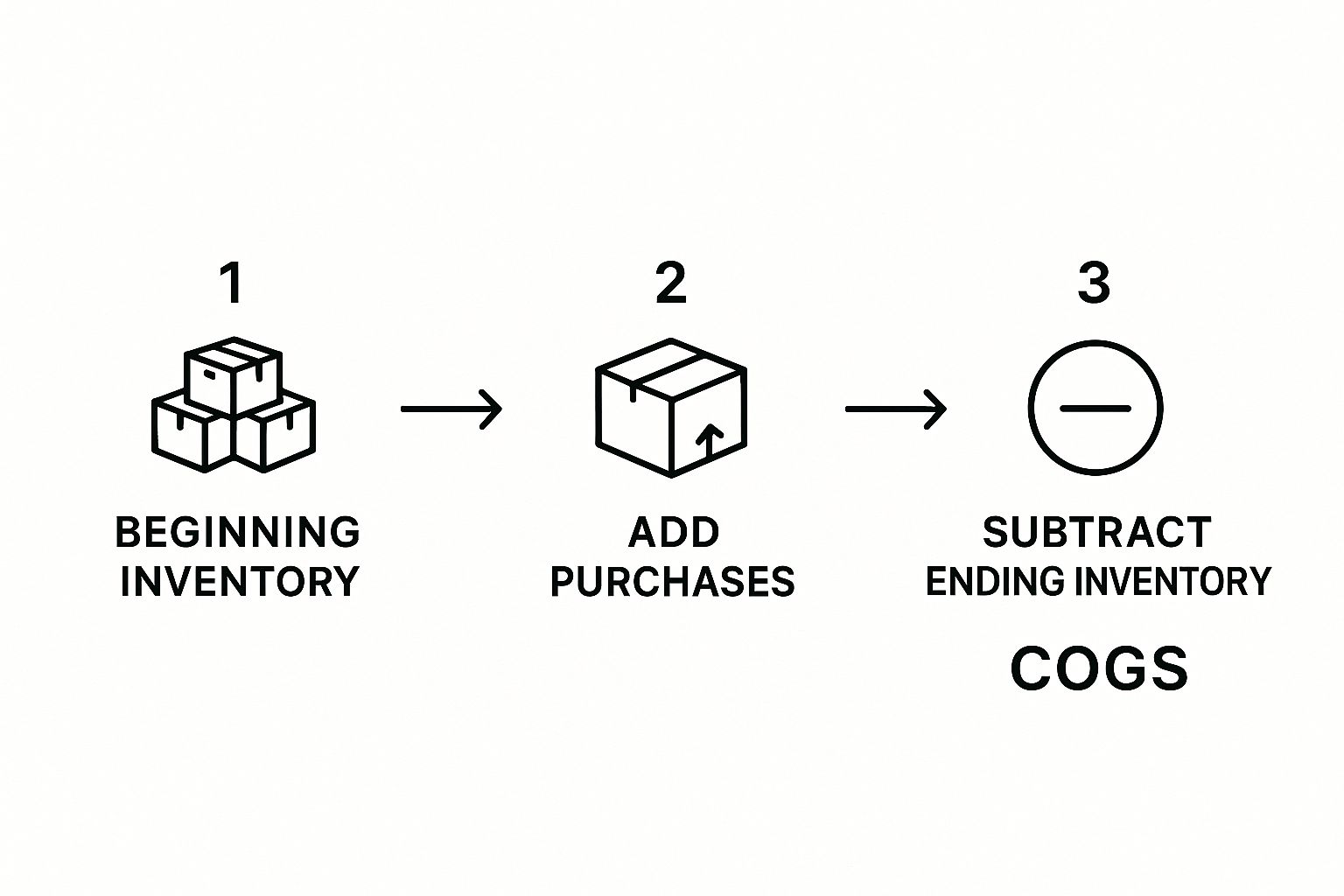

Here’s the magic formula:

COGS = Beginning Inventory + Purchases – Ending Inventory

It might look basic, but this little equation is incredibly powerful. The logic behind it is just common sense: you take what you started with, add what you bought, and then subtract what you have left. The result is the cost of everything you sold. This is a cornerstone of solid financial management and helps you understand your business’s real efficiency.

Breaking Down the Formula

Let’s quickly go through each piece so the whole thing clicks.

- Beginning Inventory: This is simply the dollar value of all the products you had on hand the moment the accounting period started. Think of it as your starting line. It’s the exact same number as your ending inventory from the period before.

- Purchases: This is the cost of any new stock you brought in during that period. And don’t forget to include extra costs like shipping or freight fees—those are part of the true cost of getting the goods ready for sale.

- Ending Inventory: This is the value of whatever is left on your shelves when the period closes. Getting this number right is critical. You’ll probably need to do a physical count, because any mistake here throws off both your COGS and your profit.

This visual shows you how those three pieces fit together perfectly.

It’s all about tracking the journey of your inventory. The formula just puts a number on the cost of the products that walked out the door with your customers.

A Quick Example in Action

Let’s make this real. Imagine you run a small t-shirt shop.

On January 1, you had $5,000 worth of shirts in stock. That’s your Beginning Inventory.

During the month, you ordered more designs and spent $3,000. That’s your Purchases.

At the end of the day on January 31, you did a count and had $4,000 worth of shirts left. This is your Ending Inventory.

Now, let’s plug it into the formula:

$5,000 (Beginning Inventory) + $3,000 (Purchases) – $4,000 (Ending Inventory) = $4,000 (COGS)

So, the direct cost of the t-shirts you sold in January was $4,000. Easy as that.

What Costs to Include in Your COGS Calculation

Alright, this is where things can get a little fuzzy for business owners. What exactly goes into your COGS calculation? It’s a common stumbling block, but there’s a simple rule of thumb to follow.

If a cost is directly tied to making the product you sell, it almost certainly belongs in COGS. Think of these as the non-negotiable expenses—without them, you literally wouldn’t have anything to put on the shelf.

The Three Core Categories of COGS

To make it easier, let’s break down these direct costs into three main buckets. Nailing these categories will help you separate what goes into COGS from your other general business expenses.

- Direct Materials: This is the obvious one. It’s the raw stuff that becomes your final product. For a furniture maker, it’s the wood, screws, and varnish. For a clothing brand, it’s the fabric, thread, and zippers.

- Direct Labor: This covers the wages for the people who are hands-on in the production process. Think about the person on the assembly line physically putting the product together—their salary is a direct labor cost. The salary for your marketing manager, on the other hand, is not.

- Manufacturing Overhead: This is for all the other factory-related costs necessary for production but not tied to a specific unit. We’re talking about the electricity bill for the factory, rent on your production space, or even supplies like glue and safety goggles.

Getting this right is crucial. It’s the only way to get a true picture of your production costs and, ultimately, your profitability.

Here’s a quick test: Ask yourself, “Does this cost go up when I make more stuff?” If the answer is yes, that’s a huge clue it belongs in COGS.

This concept even applies to businesses that don’t sell physical products. For a software-as-a-service (SaaS) company, COGS looks different but the logic is the same. Their direct costs would include things like server hosting fees from a provider like AWS or the salaries of the customer support team helping users.

On the flip side, the sales team’s commissions are an operating expense because they’re related to selling the service, not creating it. This distinction is what gives you a clear view of your real production efficiency.

How COGS Directly Affects Your Profit

Knowing what COGS is is one thing. Seeing how it chips away at your profit? That’s where the real insight is.

Think of it this way: Cost of Goods Sold is the first and biggest expense that gets taken out of your revenue. Every single dollar you can save on making or buying your products drops directly into your gross profit. That’s more cash for marketing, rent, payroll, and ultimately, for growing the business.

Rising vs. Falling COGS

A rising COGS is a warning light on your business dashboard. Are your material costs creeping up? Is your production process getting sloppy and wasteful? You need to find out, fast.

On the flip side, a falling COGS is a huge win. It’s a clear sign you’re getting smarter and more efficient at what you do.

Gross Profit: The First Look at Your Financial Health

This is where the rubber meets the road. Your gross profit tells you how much money you’ve made from your sales before you pay for all the other stuff that keeps your business running.

It’s a simple, yet powerful, formula:

Gross Profit = Total Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold

This number is the most direct measure of how well your production and pricing strategies are working together. A healthy gross profit gives you breathing room. A razor-thin one means you’re walking a financial tightrope.

Even the giants live and die by this number. For a recent fiscal year, a massive company like IBM reported a COGS of $27.20 billion. That figure shows just how critical managing direct costs is, no matter your size.

Ultimately, keeping a close eye on your COGS isn’t just about accounting. It’s about finding smart ways to implement high-impact cost reduction strategies that give you a real competitive edge. A lower COGS lets you either pocket more profit or pass those savings on to your customers with more competitive prices.

Choosing an Inventory Method That Affects COGS

Here’s where things get interesting. Your Cost of Goods Sold isn’t always a fixed number—it can actually change depending on how you decide to value your inventory. It might sound a bit odd, but the accounting method you pick directly ripples through your financial statements, even if your sales and products stay exactly the same.

Think about it this way: when you make a sale, which specific item did you sell? Was it the one that’s been sitting on your shelf the longest, or the one that just arrived yesterday? The answer to that question changes your COGS calculation, which in turn changes your profit on paper. Nailing this down is a crucial part of smart small business accounting and helps you make much better decisions for your company’s future.

FIFO: First-In, First-Out

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) method is exactly what it sounds like. It assumes that the first items you brought into your inventory are the first ones you sell. The classic example is a grocery store pushing its oldest cartons of milk to the front of the shelf. You want to sell what came in first to avoid spoilage.

When prices are on the rise (hello, inflation!), FIFO tends to give you a lower COGS. Why? Because you’re matching older, cheaper inventory costs against today’s higher sales prices. This makes your gross profit look healthier, which can be a big plus if you’re trying to impress investors or get a loan.

LIFO: Last-In, First-Out

On the flip side, we have the Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) method. This approach assumes the most recent items you purchased are the first ones to go out the door. Imagine a big barrel of nails at a hardware store—customers just grab from the top, which is always the newest stock.

In a period of rising costs, LIFO matches your newest, most expensive inventory against your revenue. This results in a higher COGS and, you guessed it, lower reported profits. The main perk here is a potential tax break, since lower profits often mean a smaller tax bill. It’s important to know, though, that LIFO isn’t allowed under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which New Zealand and many other countries follow.

Key Takeaway: Your choice of inventory method doesn’t actually change how much cash is in your bank account, but it can dramatically change your company’s profitability on paper. This single decision has real-world impacts on your taxes and business valuation.

Weighted-Average Cost Method

If trying to track every single purchase cost feels like a headache, the Weighted-Average Cost (WAC) method is your friend. It smooths out all the price bumps by calculating one average cost for all the goods you have ready to sell.

You find this average by taking the total cost of all your inventory and dividing it by the total number of items you have. This single average cost is then used to figure out both your COGS and your remaining inventory’s value. It’s a great middle-of-the-road option that gives you a more stable result than FIFO or LIFO, making it perfect for businesses selling similar, non-perishable items.

Still Have Questions About COGS?

You’re not alone. Even after you get the formula down, some tricky questions tend to pop up. Let’s run through a few of the most common ones so you can feel completely on top of this.

Think of this as your go-to cheat sheet for those “what about…” moments that every business owner faces. Nailing these details is a big step toward truly understanding your business’s financial health.

Is COGS Just Another Name for Operating Expenses?

Nope, and this is a big one to get right. They’re two totally different things.

Your Cost of Goods Sold is all about the direct costs of making what you sell. Think raw materials, the direct labor to assemble a product, or the packaging it goes in.

Operating expenses (OpEx), on the other hand, are the costs of keeping the lights on—things like your office rent, marketing budget, or the salary for your administrative staff.

Learn more:

Here’s a simple way to tell them apart: ask yourself, “If I made zero sales this month, would I still have this cost?” If the cost disappears, it’s probably COGS. If it sticks around, it’s OpEx.

What About Service Businesses? Do They Have COGS?

They sure can! It just looks a little different from a business selling, say, t-shirts. Since there are no physical “goods,” the costs are tied to delivering the service itself.

For a service business, COGS might include:

- Direct labor costs for the team members actively working on a client’s project.

- Software or tools that are essential for providing that specific service.

- Fees for contractors you bring in to help get the job done for a customer.

If a business truly has zero direct costs tied to what it sells (which is rare), then its COGS would be $0.

The key takeaway: COGS is the cost of delivering what you sold, not the cost of running the whole show.

How Do I Actually Lower My Cost of Goods Sold?

Reducing your COGS is one of the fastest ways to improve your gross profit, so it’s a fantastic goal to have.

You could try things like negotiating better deals with your suppliers for raw materials, finding ways to make your production process more efficient to cut down on waste, or even tweaking a product’s design to use less expensive materials (without skimping on quality, of course).

Need a hand sorting out your COGS from your OpEx? The team at Business Like NZ Ltd specializes in helping small businesses in Auckland gain financial clarity and freedom. Find out how we can help you at https://businesslike.sproutonline.nz.